Time keeps two clocks in spaceflight. One measures ambition, the other measures results.

We often look back at NASA’s golden age in the 60s. Apollo funding peaked at about 4.4 percent of the federal budget in 1966, then fell after the first Moon landing in 1969. Today the share is far lower while output remains strong. (The Planetary Society)

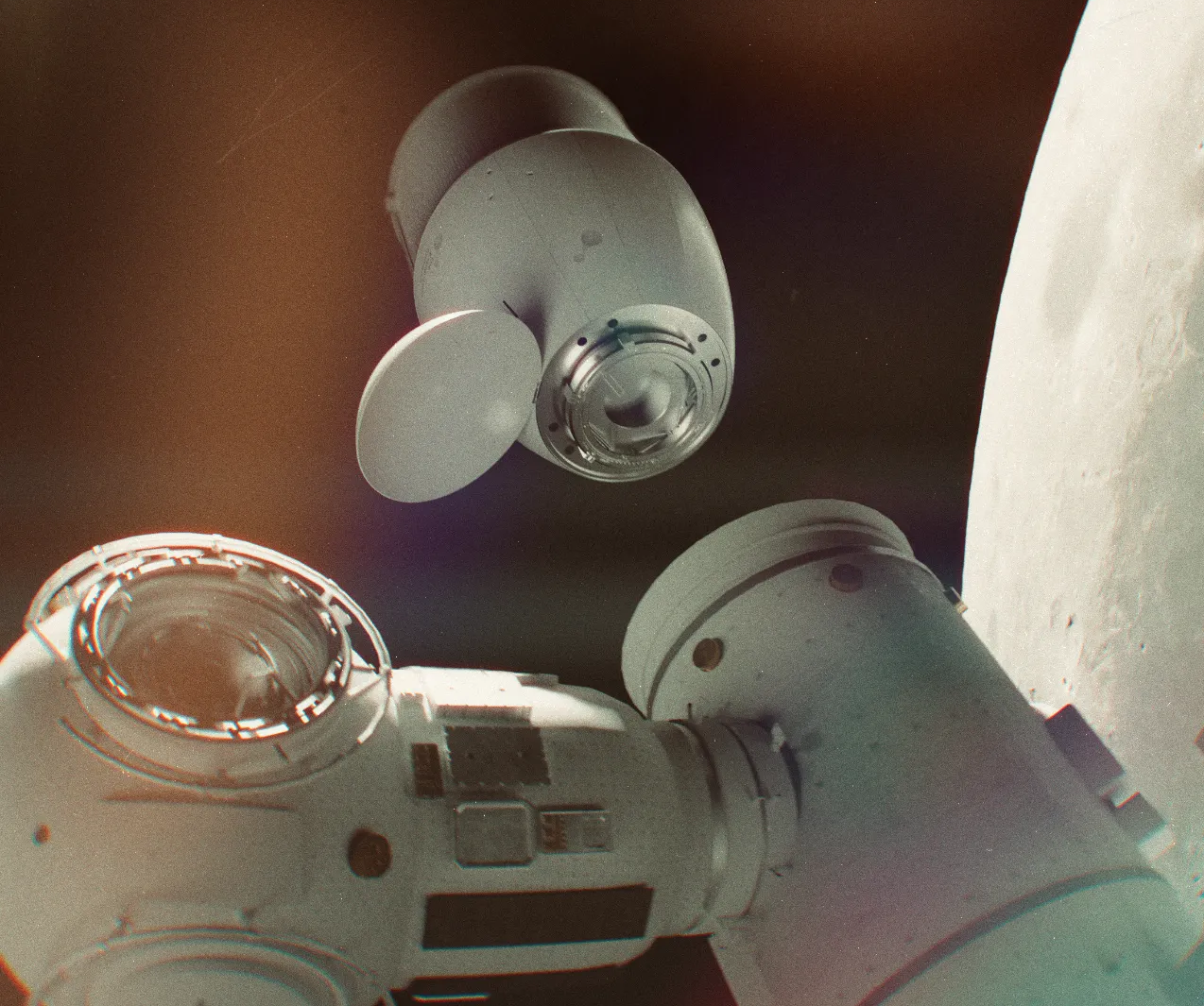

The reason is that, from the late 2000s onward, NASA learned to make the two clocks tick together. It changed how it worked with industry, moved from owning every blueprint to buying outcomes i.e., NASA acted as an anchor client and not anymore as the design authority. In a NASA Kennedy Space Center analysis, meeting the International Space Station’s cargo and crew needs through commercial services comes out at roughly 37 to 39 percent of a Shuttle continuation scenario. That shift marked the modern turn to commercial space. (NASA Technical Reports Server)

Europe’s traditional institutional path works differently. Industry or ESA forms a concept, then seeks funding commitments from member states. Governments negotiate contributions and industrial returns, often over several years. Only after the workshare is settled does full development begin. Time stretches, competition narrows, and market fit is uncertain.

Commercial space reverses the order. Industry starts with customers, gathers feedback, and invests in its own R&D or raises private funds to de-risk technology. Once there is tangible user interest, shown by letters of intent or early contracts, industry approaches ESA and member states for complementary public support. ESA then runs a competition to award service contracts. Financing countries can receive industrial returns, service returns, or both.

Because public buyers commit to purchasing services, companies can raise equity or debt to co-finance development. Private money flows when public demand is clear and performance is testable. In NASA’s experience, commercial cargo alone leveraged about 1.4 dollars from other sources for every 1 NASA dollar, an indicator of how public demand can crowd in private capital. (NASA Technical Reports Server)

The effects are practical. Buying decisions follow demonstrated capability, which shortens negotiation cycles. The burden on taxpayers falls because a meaningful share of development is carried out by private investors responding to credible demand. Jobs are more sustainable because projects grow from verified customer needs rather than theoretical demand. Most importantly, competition moves to the point that matters. Teams win work by delivering, not by negotiating workshare.

We advocate for Europe to unleash the potential of its space industry with service contracts, open competitions where all players can participate and public-private co-financing.

Hélène Huby, Founder and CEO of The Exploration Company